Rebuilding The Past: The Controversial Case of Berlin’s Stadtschloss, Part I

Posted by dmsarchitects on February 5, 2014 · Leave a Comment

This post is the first in a two-part series by DMSAS Intern Architect Julian Murphy. Before joining the firm full time last summer, Julian served as a DMSAS Travel Fellow from the University of Notre Dame. Julian graduated from Notre Dame with an BArch in May 2012.

As a part of my DMSAS travel fellowship, I visited Berlin for two weeks in the summer of 2012. The purpose of my travel was to research and document the development of the urban core of the city since the 19th century. More specifically, the focus of the trip was on the site of Berlin’s future Humboldt Forum, a proposed “cultural center” on the site of the city’s former royal palace, whose construction is currently underway.

If you want to understand the ideological tension and prevailing dogmatism that attend European postwar re/construction, Berlin is not a bad place to start. The modern German landscape, after all, still reflects a tainted 20th century, and nowhere is this more evident than in its capital city. Bombed, broken, and patched roughly back together, Berlin’s current cityscape is a dense network of remnants and reminders of a troubled past. The question of how to deal with this built history—what to save vs. what to destroy, what to memorialize vs. what to deliberately forget—is one that has been understandably mired in contention. It is all around a volatile environment, and its aspects range from the provocative to the downright puzzling (one thinks, for instance, of Berlin’s Olympic stadium, built during the reign of the Third Reich for Hitler’s dress parade that was the 1936 Olympics, and in active use today—apparently unblemished by its less than savory conception). But if you really want to see the heart of this explosive atmosphere, an issue that for decades has polarized preservationists, architects, and the public alike, you will need to head to neither a building nor a monument, but to an empty field at the historical termination of Berlin’s grand boulevard, nestled between two arms of the river Spree.

Aerial view of the site formerly occupied by the Stadtschloss

This is the site of the city’s former royal palace, or Stadtschloss, which existed on the Spree Island for nearly 500 years before being torn down after structural damage from bombing in WWII. The controversy that has surrounded the site in recent years is the result of the city’s decision in 2007 to reconstruct the historical palace. An international design competition was held, and the winning proposal by Italian architect Franco Stella is finally being built, set to be completed in 2019. That this proposal has been met with both approbation and dismay becomes clear when you understand the complex history of this site in the center of the city.

The palace was started in the mid-15th century when the Elector of the Brandenburg territory, in which Berlin was the most prominent commercial hub, forced the medieval city to give up a piece of land where he could comfortably reign. By the end of the 15th century, the palace that was built had become the permanent residence of the Hohenzollerns (the electoral family). It was also during this period that the Electorate of Brandenburg began to be recognized as one of the most powerful principalities in the region. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Berlin grew dramatically and blossomed out from the palace with the addition of a walled town and two gridded districts.

Map of 18th century Berlin

This new, larger Berlin also became a royal capital during this period. Up to this point, German sovereign princes were always subordinate (at least nominally) to the Holy Roman Emperor. But through a bit of brown-nosing diplomacy, Friedrich III, Elector at the time, convinced the emperor to grant him the title of king after the Brandenburg principality acquired the duchy of Prussia, which lay outside the Empire’s borders. And so Friedrich III became King IN Prussia (not of, because part of Prussia belonged to the Polish crown). So Berlin strangely became a royal capital, and the Stadtschloss, accordingly, a royal palace. (We are forced to wonder with what inadequacies Friedrich III must have been burdened to take such conspicuously compensatory measures.)

Friedrich III also expanded and “baroqued” the palace with the help of his court architect, Andreas Schluter. Schluter’s bold design has been praised as the crowning accomplishment of northern baroque architecture. The area surrounding the palace took its final form during the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm III in the 19th century through the efforts of the royal architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel. His masterwork, the Altes museum, was built across from the palace to the north. The area between the two buildings, the Lustgarten, which had formerly been a shapeless public green, was formalized and finally given the dignity befitting its prominent location.

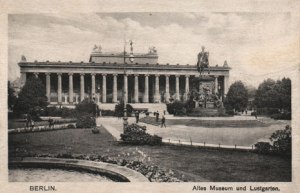

The Altes Museum and Lustgarten

The important thing to understand about the palace during this period is that it dominated Berlin both physically and symbolically, and its presence defined the city center. It was the eastern terminus of the city’s main thoroughfare—the Unter den Linden—and because the city grew from the palace’s central location, the Stadtschloss linked old and new Berlin. In addition, the Lustgarten, which had become Berlin’s most important urban space, was at the intersection of the palace and Unter den Linden.

After the post-war four-power division of Berlin, the ailing remains of the palace fell in the Soviet sector of the city. In 1950 Walter Ulbricht, leader of the Socialist Union Party, decreed the damaged building’s demolition. It was duly torn down, but for years nothing was built, and the vast site facing the Lustgarten sat empty. In the 1970’s, the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) finally constructed a new building—the Palace of the Republic, a concrete and reflective bronze glass cuboid thing, on the eastern half of the site. This building was the meeting place of the East German parliament and also housed public activities such as concerts. After the Berlin Wall came down and East and West Germany unified, parliament came to a decision to tear down the Palace of the Republic, which was allegedly contaminated with asbestos. Many thought the charge was bogus, simply an excuse to rid an important site of East German associations. People were outraged and some protested who saw the Palace of the Republic as an integral part of the historical topography of central Berlin. There proceeded a nine-year political stalemate during which the building stood empty. The decision, however, was finalized in 2003, and the Palace of the Republic ultimately demolished in 2006.

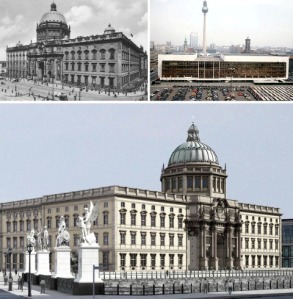

Top Left: The original Stadtschloss (1451-1950) Top Right: The Palace of the Republic (1976-2006) Bottom: A rendering of Franco Stella’s Humboldt Forum, scheduled to be complete by 2019

But the site couldn’t remain empty. For some time there had been talk of reconstructing the Stadtschloss. Art students from Paris in the early 90s had put up tromp l’oiel facades of the old building over the abandoned Palace of the Republic. This, predictably, delighted some and outraged others. But it planted the idea of reconstruction firmly in the public mind, growing strength over the years until, in 2007, reconstruction of the Stadtschloss became the official government position. But the saga of the old palace was far from over.

This series on Berlin’s Stadtschloss will continue next week. Stay tuned for part two!

Rebuilding The Past: The Controversial Case of Berlin’s Stadtschloss, Part I

Posted by dmsarchitects on February 5, 2014 · Leave a Comment

This post is the first in a two-part series by DMSAS Intern Architect Julian Murphy. Before joining the firm full time last summer, Julian served as a DMSAS Travel Fellow from the University of Notre Dame. Julian graduated from Notre Dame with an BArch in May 2012.

As a part of my DMSAS travel fellowship, I visited Berlin for two weeks in the summer of 2012. The purpose of my travel was to research and document the development of the urban core of the city since the 19th century. More specifically, the focus of the trip was on the site of Berlin’s future Humboldt Forum, a proposed “cultural center” on the site of the city’s former royal palace, whose construction is currently underway.

If you want to understand the ideological tension and prevailing dogmatism that attend European postwar re/construction, Berlin is not a bad place to start. The modern German landscape, after all, still reflects a tainted 20th century, and nowhere is this more evident than in its capital city. Bombed, broken, and patched roughly back together, Berlin’s current cityscape is a dense network of remnants and reminders of a troubled past. The question of how to deal with this built history—what to save vs. what to destroy, what to memorialize vs. what to deliberately forget—is one that has been understandably mired in contention. It is all around a volatile environment, and its aspects range from the provocative to the downright puzzling (one thinks, for instance, of Berlin’s Olympic stadium, built during the reign of the Third Reich for Hitler’s dress parade that was the 1936 Olympics, and in active use today—apparently unblemished by its less than savory conception). But if you really want to see the heart of this explosive atmosphere, an issue that for decades has polarized preservationists, architects, and the public alike, you will need to head to neither a building nor a monument, but to an empty field at the historical termination of Berlin’s grand boulevard, nestled between two arms of the river Spree.

Aerial view of the site formerly occupied by the Stadtschloss

This is the site of the city’s former royal palace, or Stadtschloss, which existed on the Spree Island for nearly 500 years before being torn down after structural damage from bombing in WWII. The controversy that has surrounded the site in recent years is the result of the city’s decision in 2007 to reconstruct the historical palace. An international design competition was held, and the winning proposal by Italian architect Franco Stella is finally being built, set to be completed in 2019. That this proposal has been met with both approbation and dismay becomes clear when you understand the complex history of this site in the center of the city.

The palace was started in the mid-15th century when the Elector of the Brandenburg territory, in which Berlin was the most prominent commercial hub, forced the medieval city to give up a piece of land where he could comfortably reign. By the end of the 15th century, the palace that was built had become the permanent residence of the Hohenzollerns (the electoral family). It was also during this period that the Electorate of Brandenburg began to be recognized as one of the most powerful principalities in the region. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Berlin grew dramatically and blossomed out from the palace with the addition of a walled town and two gridded districts.

Map of 18th century Berlin

This new, larger Berlin also became a royal capital during this period. Up to this point, German sovereign princes were always subordinate (at least nominally) to the Holy Roman Emperor. But through a bit of brown-nosing diplomacy, Friedrich III, Elector at the time, convinced the emperor to grant him the title of king after the Brandenburg principality acquired the duchy of Prussia, which lay outside the Empire’s borders. And so Friedrich III became King IN Prussia (not of, because part of Prussia belonged to the Polish crown). So Berlin strangely became a royal capital, and the Stadtschloss, accordingly, a royal palace. (We are forced to wonder with what inadequacies Friedrich III must have been burdened to take such conspicuously compensatory measures.)

Friedrich III also expanded and “baroqued” the palace with the help of his court architect, Andreas Schluter. Schluter’s bold design has been praised as the crowning accomplishment of northern baroque architecture. The area surrounding the palace took its final form during the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm III in the 19th century through the efforts of the royal architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel. His masterwork, the Altes museum, was built across from the palace to the north. The area between the two buildings, the Lustgarten, which had formerly been a shapeless public green, was formalized and finally given the dignity befitting its prominent location.

The Altes Museum and Lustgarten

The important thing to understand about the palace during this period is that it dominated Berlin both physically and symbolically, and its presence defined the city center. It was the eastern terminus of the city’s main thoroughfare—the Unter den Linden—and because the city grew from the palace’s central location, the Stadtschloss linked old and new Berlin. In addition, the Lustgarten, which had become Berlin’s most important urban space, was at the intersection of the palace and Unter den Linden.

After the post-war four-power division of Berlin, the ailing remains of the palace fell in the Soviet sector of the city. In 1950 Walter Ulbricht, leader of the Socialist Union Party, decreed the damaged building’s demolition. It was duly torn down, but for years nothing was built, and the vast site facing the Lustgarten sat empty. In the 1970’s, the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) finally constructed a new building—the Palace of the Republic, a concrete and reflective bronze glass cuboid thing, on the eastern half of the site. This building was the meeting place of the East German parliament and also housed public activities such as concerts. After the Berlin Wall came down and East and West Germany unified, parliament came to a decision to tear down the Palace of the Republic, which was allegedly contaminated with asbestos. Many thought the charge was bogus, simply an excuse to rid an important site of East German associations. People were outraged and some protested who saw the Palace of the Republic as an integral part of the historical topography of central Berlin. There proceeded a nine-year political stalemate during which the building stood empty. The decision, however, was finalized in 2003, and the Palace of the Republic ultimately demolished in 2006.

Top Left: The original Stadtschloss (1451-1950) Top Right: The Palace of the Republic (1976-2006) Bottom: A rendering of Franco Stella’s Humboldt Forum, scheduled to be complete by 2019

But the site couldn’t remain empty. For some time there had been talk of reconstructing the Stadtschloss. Art students from Paris in the early 90s had put up tromp l’oiel facades of the old building over the abandoned Palace of the Republic. This, predictably, delighted some and outraged others. But it planted the idea of reconstruction firmly in the public mind, growing strength over the years until, in 2007, reconstruction of the Stadtschloss became the official government position. But the saga of the old palace was far from over.

This series on Berlin’s Stadtschloss will continue next week. Stay tuned for part two!

Share this:

Related

Filed under Commentary, Design · Tagged with architecture, DMSAS, Fellowship, Germany, planning, urban